-40%

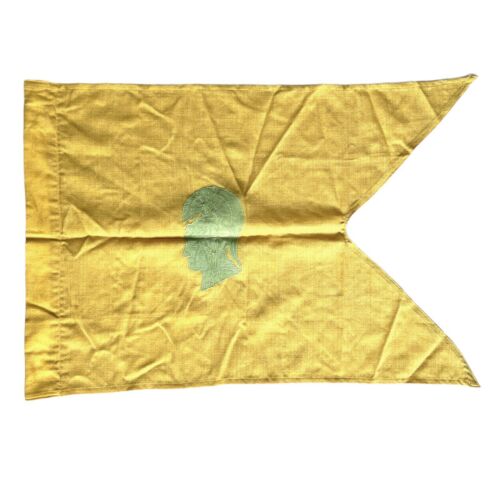

WWII Jeep Guidon, Co “A”, 7th Cavalry Regiment; C/O Jeep Antenna Flag 1945-1949

$ 211.2

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Post WWII C/O Jeep Guidon * Company “A”, 7th Cavalry Regiment Circa 1949 Japanese OccupationFor your consideration is this Company “A”, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, 8th Army C/O Jeep Guidon for the Occupation of Japan circa 1949.

This is a theater made guidon. This piece is made of wool bunting with cotton linen letter/number appliqué on both sides. This piece has a sleeve and leather tabs. This is a 1-sided guidon with very minor staining. This C/O Jeep Guidon measures 16 in x 24 in.

Japan Occupation; 7th Cavalry Linage

1945-1949 Japan: Occupation Forces (1st Cavalry Division /8th Army)

•1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry; Troops "A", "B", "C", & "D"

•2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry; Troops "E", "F", "G", & "H"

1949 Japan: Occupation Forces (1st Cavalry Division /8th Army)

•1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry; re-designated

Company "A", 7th Cavalry

•2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry; re-designated

Company "B", 7th Cavalry

•3rd Squadron, 7th Cavalry; re-designated

Company "C", 7th Cavalry

•4th Squadron, 7th Cavalry; re-designated

Company "D", 7th Cavalry

1949 - Japan; Occupation Force (1st Cavalry Division/ 8th Army)

•1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry "A" Company re-designated

1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry "A", "B", "C", & "D"

•2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry "B" Company re-designated

2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry "E", "F", "G", & "H"

•3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry "C" Company re-designated

3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry "I", "K", "L" & "M"

HISTORY 7th Cavalry : 1941-1950

On 7 December 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked the US fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, thrusting the United States into World War II, which had already been raging since 1939. The Troopers of the 1st Cavalry Division readied their horses, their equipment, and themselves for the coming war, and were finally alerted for deployment in 1943. Despite being a mounted Cavalry unit since 1866, the 7th Cavalry left its mounts behind in Texas as they left for war; the age of the horse-cavalry was over. The newly dismounted 7th Cavalry Regiment was sent to fight in the Pacific Theater of Operations and the last units left Fort Bliss for Camp Stoneman, CA in June 1943. On 3 July, the 7th Cavalry boarded the SS Monterey and the SS George Washington bound for Australia. The Regiment arrived on 26 July, and was posted to Camp Strathpine, Queensland where they underwent six months of intensive jungle warfare training, and conducted amphibious assault training at nearby Moreton Bay.

Admiralty Islands campaign

In January 1944, the 7th Cavalry sailed for Oro Bay on the island of New Guinea. Despite the ongoing New Guinea Campaign, the 7th Cavalry was held in reserve and was organized into "Task Force Brewer" for another mission. On 27 February, TF Brewer embarked from Cape Sudest under the command of Brigadier General William C. Chase. Their objective was the remote Los Negros Island in the Admiralty Islands which had an important airfield occupied by the Japanese. The 5th Cavalry Regiment landed on 29 February and began the invasion.

The morning of 4 March saw the arrival of the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry, which relieved the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry. The next day Major General Innis P. Swift, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, arrived aboard Bush and assumed command. He ordered the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry to attack across the native skidway. The 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry therefore went back into the line to relieve them. While the relief was taking place, the Japanese launched a daylight attack. This was repulsed by the cavalrymen, with the help of artillery and mortar fire, but the American attack was delayed until late afternoon. It then ran into a Japanese minefield and by dawn the advance had only reached as far as the skidway. On the morning of 6 March, another convoy arrived at Hyane Harbour: five LSTs, each towing an LCM, with the 12th Cavalry and other units and equipment including five Landing Vehicles Tracked (LVTs) of the 592nd EBSR, three M3 light tanks of the 603rd Tank Company, and twelve 105mm howitzers of the 271st Field Artillery Battalion. The 12th Cavalry was ordered to follow the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry in its advance to the north, and to capture the Salami Plantation. The road to Salami was little more than a muddy track in which vehicles soon became bogged. The Japanese also obstructed the route with ditches, felled trees, snipers, and booby traps. Despite incessant rain and suicidal Japanese counterattacks, the 7th Cavalry captured their objectives and mop-up operations were being conducted from 10–11 March. Manus Island, to the west, was the next target.

The main landing was to be at Lugos Mission, but General Swift postponed the landing there and ordered the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry to capture Hauwei. The landing was covered by the destroyers Arunta, Bush, Stockton and Thorn; a pair of rocket-firing LCVPs and the LCM (flak), which fired 168 4.5-inch (114 mm) rockets; the guns of the 61st Field Artillery Battalion on Los Negros; and six Kittyhawks of No. 76 Squadron dropped 500-pound (230 kg) bombs. The assault was made from three cargo-carrying LVTs. To save wear and tear, they were towed across Seeadler Harbour by LCMs and cut loose for the final run in to shore. The cavalrymen found well constructed and sited bunkers with interlocking fields of fire covering all approaches, and deadly accurate snipers. The next morning an LCM brought over a medium tank, for which the Japanese had no answer, and the cavalrymen were able to overcome the defenders at a cost of eight killed and 46 wounded; 43 dead Japanese naval personnel were counted.

The 8th Cavalry Regiment began the main assault on Manus on 15 March and attacked the important Lorengau Airfield on 17 March. After initially quickly overrunning the enemy positions, the cavalry resumed its advance, and occupied a ridge overlooking the airstrip without opposition. In the meantime, the 7th Cavalry had been landed at Lugos from the LST on its second trip and took over the defense of the area, freeing the 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry to join the attack on Lorengau. The first attempt to capture the airstrip was checked by an enemy bunker complex. A second attempt on 17 March, reinforced by the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry and tanks, made good progress. The advance then resumed, with Lorengau itself falling on 18 March.

Although there had been plenty of fighting, the main Japanese force on Manus had not been located. Advancing inland towards Rossum, the 7th Cavalry found it on 20 March. Six days of fighting around Rossum were required before the 7th and 8th Cavalry reduced the entrenched Japanese positions there. The Japanese bunkers, actually log and earth pillboxes, proved resistant to artillery fire. These weary Troopers were relieved by the 7th Cavalry on 18 March. That day, the 7th Cavalry attacked, and drove the enemy out of Lorengau Village.

The Admiralty Islands campaign ended on 18 May 1944 with the islands and airfields secured and 3,317 Japanese dead. The 7th Cavalry Regiment suffered 43 killed in action, 17 wounded, and 7 dead from non-battle injuries. Having faced down suicidal Japanese counterattacks and a stubborn defense in the rainy jungles of the Southwest Pacific, the 7th Cavalry Troopers were now veterans.

Battle of Leyte

After a period of 5 months in rehabilitation and extensive combat training, the 7th Cavalry Regiment received instructions on 25 September 1944 to prepare for future combat operations. On 20 October, the regiment began the assault of Leyte Island.

The Battle of Leyte began when the first waves of the 7th Cavalry Regiment stormed ashore at White Beach at 1000, H-Hour, and were met with small arms and machine gun fire. 1st Squadron-7th Cavalry Regiment (1-7 Cavalry) landed on the right flank and was to attack north into the Cataisan Peninsula to capture Tacloban Aerodrome. To the left, 2-7 Cavalry was to attack inland, capture San Jose, and seize a beachhead line west of Highway 1. They were met with slight opposition, and within the first 15 minutes, 2-7 Cavalry knocked out two Japanese defensive pillboxes firing into the landing zone. After a house-to-house assault, San Jose was captured by 1230. 2-7 Cavalry's largest obstacle was the terrain. "Directly beyond the landing beaches the troops ran into a man-enveloping swamp. All along the line, men cursed as they wallowed toward their objective in mud of arm-pit depth. This unexpectedly tough obstacle however, failed to deter their dogged advance. " By 1545 2-7 Cavalry had crossed Highway No 1. Meanwhile, 1-7 Cavalry, under the command of Major Leonard Smith, had secured the Cataisan Peninsula and the Tacloban Airfield with the aid of the 44th Tank Battalion. All the 7th Cavalry's A-Day objectives had been seized before nightfall.

The following day, 21 October 1944, saw 7th Cavalry begin the attack on Tacloban. At 0800, the 1st and 2nd Squadrons advanced abreast toward the city. 1-7 Cavalry entered the city and were overwhelmed by crowds of exuberant Filipinos giving them gifts of eggs and fruit. 2-7 Cavalry, meanwhile, was halted by a force of 200 Japanese entrenched in prepared fighting positions. The Regimental Weapons Troop and Anti-Tank Platoon arrived to break the stalemate but were quickly pinned down by machine gun fire from a bunker as well. PFC Kenneth W. Grove, an ammunition carrier, singlehandedly cut through the jungle, charged the bunker and killed the weapons crew, and allowed the advance to resume. By the end of 22 October the capital of Leyte and its hill defenses were securely in American hands. The 7th Cavalry was one day ahead of schedule, a fact partly explained by the unexpectedly light resistance of the Japanese and partly by the vigor of the 7th Cavalry's advance.

On 23 October, the 7th was relieved by the 8th Cavalry and prepared to undertake operations to secure the San Juanico Strait across from the island of Samar. On 24, 1 October- 7 Cavalry landed at Babatngon at 1330 and sent out patrols to secure the beachhead. The landing was unopposed, and 1-7 Cavalry made several other over-water movements to secure the area, making the most of the scant Japanese resistance. By 27, 7 October Cavalry (minus 1st Squadron) was in reserve. 1-7 Cavalry, in Babatngon, was ordered to secure the Barugo and Carigara area. Troop C, under 1LT Tower W. Greenbowe, advanced on 28 October without incident, but received fire from Carigara. In the ensuing firefight, C Troop eliminated 75 enemies at the cost of 3 killed, 9 wounded, and 1 missing (the mutilated body of the missing man was found later) before withdrawing to Barugo, where it was joined by the rest of the Squadron on the 29th for an assault on Carigara. On 2, 1 November- 7 Cavalry attacked across the Canomontag River by using 2 native canoes, and occupied Carigara by 1200 with no resistance.

After remaining in a reserve role, 2-7 Cavalry relieved elements of the 12th Cavalry operating in the central mountain range of the island. Between 11 and 14 December, they continually assaulted a series of well-defended ridges and hills and only were able to wrest control over them by calling in over 5,000 rounds of artillery support. The 1st Cavalry Division continued to push west toward the coast through the mountainous and dense jungle interior of the island. On the morning of 23 December 1944, 1st Squadron-7th Cavalry assault units pushed across Highway 2 and set up night positions on line with the other divisional units. They pushed off for the attack the next morning meeting only scattered resistance. By 29, 7 December Cavalry units reached the west coast, north of the village of Tibur, and drove north, capturing the town of Villaba, and killing 35 Japanese there. On 31 December, the Japanese launched four counterattacks on the 7th Cavalry, each starting with a bugle call. The first occurred at 0230 and the last one was at dawn. An estimated 500 enemy attacked the positions, but they were driven off by the stalwart defenders and by American artillery superiority. 77th Infantry Division elements began relieving the 7th Cavalry later that day. Leyte was soon declared secure, despite the large number of Japanese soldiers remaining hidden in the thick jungle of the island's interior, and elements of the 7th Cavalry were kept busy by conducting mop-up missions and patrols until their next big operation.

Battle of Luzon

For the forces of General MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area the reconquest of Luzon and the Southern Philippines was the climax of the Pacific war. Viewed from the aspect of commitment of U.S. Army ground forces, the Luzon Campaign (including the seizure of Mindoro and the central Visayan Islands) was exceeded in size during World War II only by the drive across northern France. The Luzon Campaign differed from others of the Pacific war in that it alone provided opportunity for the employment of mass and maneuver on a scale even approaching that common to the European and Mediterranean theaters.

The initial Army units in the invasion had landed on 9 January and secured a beachhead, but GEN MacArthur needed more forces on the island to begin his drive to Manila. Despite not receiving adequate rest and replacements from the Battle of Leyte, the 1st Cavalry Division was sent ahead to take part in the Battle of Luzon and landed in Lingayen Gulf on 27 January 1945. The 7th Cavalry quickly moved inland toward Guimba, but as A Troop passed through Labit, they were attacked by a Japanese ambush unit. Technical Sergeant John B. Duncan, of Los Angeles, CA, was cited for his courageous and determined effort to drive the attackers back. He succeeded in doing so, but was mortally wounded. GEN MacArthur ordered that the 1st Cavalry Division assemble three "Flying Columns" for the drive on Manila. The 7th Cavalry was tasked with providing security for them. As elements of the 8th Cavalry swung south, the 7th Cavalry advanced by foot and kept the Japanese occupied while their counterparts broke through. On 4 February 1945, LTC Boyd L. Branson, the Regimental operation officer from San Mateo, CA, earned the Silver Star by voluntarily leading the advance units over more than 40 miles of un-reconnoitered, enemy-held terrain. While the rest of the Division was fighting in Manila, the 7th Cavalry engaged the enemy near the Novaliches watershed east of the city to prevent their reinforcement. On 20 February, they handed over their positions to elements of the 6th Infantry Division and moved south to begin the attack on the Shimbu Line.

Attacking eastward on the 20th, 2-7 Cavalry spearheaded deep into the Japanese line but were quickly fired upon by a heavy barrage of artillery. Drawing on their experiences from the Admiralties and Leyte for attacking entrenched enemy positions in mountainous jungle terrain, the Troopers advanced and destroyed the pillboxes and mortar positions. By 25 February, the 7th Cavalry was 2 kilometers from their objective at Antipolo. The advance continued, and on 4 March, the 7th Cavalry was hit by a strong Japanese counterattack that managed to destroy two of the American's supporting tanks before it was defeated. The battle for Antipolo was marked by bitter struggle in unforgiving terrain, and the 1st Cavalry Division was relieved by the 43rd Infantry Division on 12 March after finally capturing the ruined village. Out of the 92 Silver Stars awarded to men of the 1st Cavalry Division in their drive to Antipolo, the largest share went to men of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, with 41 being awarded. PFC Calvin T. Lewis, of Glasgow, KY, B Troop 7th Cavalry, was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism in defeating an enemy bunker. After his platoon was halted by accurate machine gun fire from a concealed bunker, he volunteered to go find it. Wielding a Browning Automatic Rifle, he located the position and poured heavy and accurate fire through the bunker's opening. After pinning the enemy down, he moved up and fired into the opening from close range, but was mortally wounded in doing so. Despite his wounds he continued to engage the enemy until all were killed.

After being relieved in their sector on 20 April, the 7th Cavalry prepared for another mission; the capture of Infanta to the south. On 6 May 1945 the 7th Cavalry began moving south into the Santa Maria Valley toward Lamon Bay along Route 455. Along the hairpin curves of the highway, they encountered tough Japanese resistance at the Kapatalin Sawmill. For several days the advance was stalled as patrols reconnoitered the position and pinpointed targets for US Army Air Corps planes. They overran the enemy by mid-afternoon of 291. They had killed 350 Japanese for the loss of 4 KIA and 17 WIA. They reached Lamon Bay on 292. Sweeping aside Japanese resistance on their march to the coast, the 7th Cavalry Troopers occasionally encountered determined defenders, and the fighting along the advance was characterized by small unit action. On 293, A Troop was moving to Real when the lead platoon was pinned down by enemy rifle and machine gun fire. Thinking quickly, Lieutenant Joe D. Crane of Athens, TX led his platoon in a flanking maneuver and annihilated the enemy force, saving his comrades. Near Gumian on 294, D Troop was attacked by a large force of 150 Japanese with machine guns, mortars, grenades, and rifles. The foliage was thick enough to conceal the enemy, allowing them to come within ten yards of the Cavalrymen's positions before being detected. LT Charles E. Paul of Camden, AR moved to an observation post in the thick of the fighting and called in close and accurate mortar fire, driving the enemy away, and earning the Silver Star for his actions. Accompanied by Philippines guerrillas, the 7th Cavalry captured Infantry on 295 and soon after secured the surrounding rice-fields. They remained here for some time patrolling the area for Japanese holdouts. By 1 June 1945, most of southern Luzon was in American hands, but there were still determined Japanese forces in the area. On 2, 30 June Japanese attacked F Troop's positions just before dawn broke and the Americans were forced to fight in hand-to-hand combat. SGT Jessie Riddell of Irvine, KY earned his second Silver Star in this attack when he saw one of his Troopers in a death struggle with a Japanese officer wielding a samurai sword. SGT Riddell ran to his aid, shooting 3 attackers on the way, and killed the enemy officer before he could kill the American.

Continuing their patrolling of southern Luzon, a patrol from B Troop ran into an unexpectedly heavy ambush on 19 June 1945. Despite the shock of the ambush, PVT Bernis L. Stringer of Visalia, CA, the patrol's BAR-man, ran forward, killing one Japanese and wounding another. He then reloaded in plain sight of the last enemy soldier before dispatching him too. PVT Stringer lost his life soon after in the closing days of the campaign. The Battle of Luzon was officially declared over on 30 June 1945 but scattered Japanese resistance remained. The battle was the longest the 7th Cavalry had fought in World War II, and it would be their last. After pulling out of the combat zone on 4 July, The regiment began to rest and refit as it prepared for the inevitable invasion of the main Japanese islands. On 20 July, the 7th Cavalry again reorganized—this time entirely under Infantry Tables of Organization & Equipment, but still designated as a Cavalry Regiment, in order to bring it up to the full strength of a 1945 Army infantry regiment. Thankfully for the men of the 7th Cavalry, the invasion was terminated after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the Japanese to surrender. 7th Cavalry Regiment was at Lucena, Tayabas (now. Quezon) in the Philippines until 2 September 1945, when it was moved to Japan to start occupation duty.

Occupation of Japan

On 13 August 1945, the 7th Cavalry was alerted that it would accompany General Douglas MacArthur to Tokyo and would be part of the Eighth Army's occupation force. On 2 September, the 7th Cavalry landed in Yokohama and began setting up a base of operation. On 8 September, the 1st Cavalry Division sent a convoy under Major General William C. Chase from Hara-Machida to Tokyo to occupy the city. This convoy was made up of one combat veteran from every Troop in the division, and it marched through Hachiōji, Fuchū, and Chōfu before reaching Tokyo; this convoy of the 1st Cavalry Division, with many veterans of the 7th Cavalry Regiment in the ranks, became the first Allied unit to enter the city. The 7th Cavalry set its headquarters at the Japanese Imperial Merchant Marine Academy and were assigned to guard the US embassy and GEN MacArthur's residence. For five years they remained in Tokyo. On 25 March 1949, the 7th Cavalry was reorganized under a new table of organization, and its Troops were renamed Companies as in a standard infantry division.